Federal Judge’s Dismissal in Smithsonian 'X' Formerly Twitter Case Draws Attention for Tone, Delay, and Critical Error

Free Speech - A federal judge’s curious ruling, a misspelled name, and a lingering constitutional question: Is the Smithsonian above the law—or bound by it?

The case traces back to Raven’s legal challenge alleging that Kim Sajet violated his constitutional rights by blocking him from the Smithsonian’s once-official @NPGDirector Twitter account—now privatized following public exposure during Raven’s earlier lawsuit. That litigation revealed that Sajet had used the government-affiliated social media page to post personal content, including photos of her participation in the anti-Trump Women’s March on January 21, 2017.

Relying heavily on the legal arguments developed in the landmark Knight First Amendment Institute v. Trump case, Raven, who is representing himself pro se, filed a detailed complaint substituting his own facts and parties into that precedent. The case gained enough traction that Judge Cooper denied the Smithsonian’s motion to dismiss, pending the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Lindke v. Freed, a parallel social media First Amendment case.

But when Lindke was decided in March 2024—largely favoring plaintiffs in situations similar to Raven’s—Judge Cooper did not promptly issue a ruling. Instead, the case lingered for months. Raven filed a motion to compel a decision. When that was ignored, he escalated the matter with an emergency interlocutory petition to the U.S. Supreme Court, citing SCOTUS precedents urging swift rulings in cases involving potential ongoing First Amendment violations.

Shortly thereafter, Judge Cooper issued his final memorandum opinion—and it was striking. The opinion opened with a tone Raven described as “hostile,” and concluded with an unforced error: the judge misidentified the plaintiff, referring to Raven as “Rajet.” For a federal court ruling—typically reviewed by clerks and revised for accuracy—such a basic mistake, especially involving parties’ names, is rare and troubling.

Legal observers note that this misnaming may reflect more than just a typo. “It’s hard to imagine that a federal judge would conflate the name of the plaintiff with the defendant, particularly in a case hinging on public speech and institutional conduct,” said one D.C.-area legal scholar, who asked not to be named. “It weakens public perception of fairness in the judiciary.”

Raven contends the misnaming—and the months-long delay following a clear Supreme Court directive—may illustrate a broader issue: reluctance within the judiciary to challenge powerful government-adjacent institutions like the Smithsonian. "When the legal tide turned in my favor, Judge Cooper stalled. I believe the delay was intentional. It felt like an effort to run out the clock rather than uphold the law," Raven said.

Indeed, the federal docket reveals Raven filed multiple motions: an opposition to the motion to dismiss, a supplemental brief after Lindke, a motion to compel, and the emergency petition to SCOTUS—all public and available for inspection. Judge Cooper’s opinion, now public as well, may become a subject of legal critique, both for its substance and judicial tone.

Meanwhile, Raven has returned to the U.S. Supreme Court with a petition for rehearing in his earlier, related case (17-cv-01240 TNM), pointing to contradictions between recent court rulings and public statements by Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch III. In a press release responding to President Trump’s recent call to fire Kim Sajet, Secretary Bunch asserted that the Smithsonian is an “independent entity”—a characterization seemingly at odds with the Smithsonian’s courtroom defense, in which it claimed to be a fully federal agency entitled to immunity under the government speech doctrine.

In a 2019 ruling in Raven’s prior case, Judge Trevor McFadden wrote that the Smithsonian was “the government through and through.” That ruling supported the Institution’s claim that it could reject Raven’s artwork submission without triggering First Amendment protections. But Bunch’s recent public statement complicates that narrative—and Raven argues it may reopen constitutional questions about the Smithsonian’s identity under law.

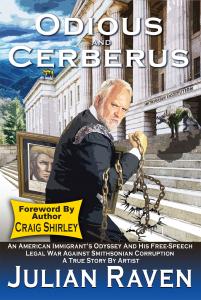

“What is the Smithsonian?” Raven asks. “Is it a public trust or a federal agency? Does it honor free speech—or circumvent it? These are not academic questions. They affect every American who engages with our national museums.” Raven claims, His book 'Odious and Cerberus: An American immigrant's odyssey and his free-speech legal war against Smithsonian corruption' answers these and other pressing constitutional questions surrounding the Smithsonian Institution.

As Raven awaits word from the Supreme Court on whether it will rehear his case, one thing remains clear: with trust in the federal judiciary at historic lows, cases like Raven v. Sajet are increasingly seen not as legal footnotes, but as indicators of whether ordinary citizens still have a voice in court.

Julian Raven

Julian Raven Artist

email us here

Distribution channels: Human Rights, Law, Media, Advertising & PR, Religion, U.S. Politics

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Submit your press release